TIME FOR A ROLEX

In 670AD the fifth patriarch of the Dongshan Monastery in Guangzhou held a competition to decide who would take over from him. In the monastery there was a Bodhi Tree and the monks claimed that it was an off shoot of the one that the Buddha meditated under. So, the patriarch asked the monks to write a poem about this tree. The head monk, Shenxiu, a great and wise scholar who was expected to do well, came up with:

The body is the bodhi tree

and the mind is like a clear mirror.

At all times we must strive to polish it,

so as not to let the dust collect.

Considerably later than 670AD, I visited the monastery, and when the monks weren’t looking, I took a twig from that tree. It went into a display cabinet in my living room but was lost after I moved house from Hong Kong to Malaysia. It probably got thrown out entangled in the copies of the South China Morning Post I packed my treasures in.

In my cabinet it was a story I told whenever anyone wondered why I had a desiccated old twig on display. It gathered dust along with all the other mementoes: the Mao badges, the Buddha busts, the bronze dragons, the wooden elephants, the old coinage from my travels. But now it would not collect dust any more, at least not my dust.

I am sure I took a photo of the twig plucking. It was probably a bad photo, and now faded to a pale yellow, like all the old undecipherable photos I put in boxes long discarded. Time it seems is cleaning that mirror or at least my constant moves. And now, without evidence to the contrary, did the twig plucking actually happen? Or is it just an embellishment that I made up to make my story of visiting China sound more interesting than a mere tourist jaunt?

Our memory constantly fails to alert us to what is real and what is merely imagined. We wake, having spent no time at all asleep, and things slip from our dreams into our minds. As the monks would say, everything is an illusion, especially our retelling of distant times. And time, I am sure the monks would tell me, is especially an illusion!

When we are in a hurry, we await the train that takes an eternity to come. And when we are hurtling through a crowded railway station trying to catch the last train home, it leaves ten seconds early, leaving us watching it retreat into the distance. Not that monks spend a lot of time rushing for trains but trains and time are metaphorically related in Western minds. Ask any passing monk and he will tell you how we all live in our own reality, piecing together our whys, whens and hows, and the past slips into a timeless dream and the future is never now. Though he is more likely to just give you a blank stare which I am sure will be interpreted as speaking volumes.

Our memories are moments of desire seen in retrospect: moments of missed opportunity, moments of misdirected affection, moments of unnecessary embarrassment, moments of tragic annihilation that we never thought we could recover from, but must have otherwise we wouldn’t be here to contemplate such things. The person looking back though, is no longer that other – the one with the funny hair and strange fashions seen in photographs. That person was from another time, another place, another life, now barely of any significance. And I can see why any decent Zen Buddhist considers it comforting to dismiss it all as an illusion.

In short, everything turns into an unmarked grave, even my parents who were there at the Monastery with me. It was their only visit when I lived in Hong Kong. So to entertain them and display my comfort and ease in negotiating the mysteries of the orient, I took them around Guanzhou.

They no longer exist and the photos of their visit cannot be found. I am older now than they were then and flatter myself by believing that I am never as confused and befuddled as they seemed to have been at such an age. They had stepped momentarily into my universe, a universe they never imagined would be part of their fate. As for myself I believe I am well practiced in stepping into other people’s universes, though my present address back in a chilly UK winter is stretching my self-confidence somewhat.

Time and space and melancholy are inextricably linked. Time here is not the same as time there. Catch a plane, and if you cross the dateline, you can arrive the day before you left. Your watch will tell you one time, but it will run strangely faster than when you were flying. Perhaps my parents’ confusion was as much jet lag as culture shock. Perhaps my present disquiet is as much to do with the UK being all too reminiscent of the one I left back in the 1980’s, bar the present obsession with tattoos and obesity. The 21st century for me has always had a Japanese design and robot dogs, whereas the UK still could be recognised by the average medieval prince chasing deer with his hounds. A British fantasy of timelessness tradition is entertained. It drove me nuts. Get with the programme I would say! Though actually what I would say back in 1980 is put them all up against the wall for, as the song goes, “The times, they are a-changing!”

Einstein once had the job of working out railway timetables when every town’s clock ran by its own time. The telegraph was used to broadcast the standard time agreed upon by the railway companies. But Einstein said he never found out how to make watches on a moving train tell the same time as the place they passed through, no matter how much corporate money was poured into the project. And he was never sure whether the train left the station or the station left the train. Everyone, he said, stands still, alone in their own frame of reference. Everything moves around them, and, I assume, everyone awaits the impact of a universal connection, a connection that subsequent scientists have discovered depends on how you measure it and can be influenced by anywhere in the universe. I certainly know that feeling! Einstein was probably as fond of tequila as I am.

My father, an inveterate whisky drinker, said he thought the Chinese, living bombarded by state propaganda, must be in a constant dream and forever frustrated by reality. He was a reader of the Daily Mail, which I pointed out to his annoyance, was perhaps not the best conduit to an appreciation of the real world. My father and I were not in sync. And maybe if Einstein had had Wi-Fi, then he might have managed to keep watches synchronised, sort of. Though even he was never in sync with his father regardless of the Einstein’s favourite tipples. Fathers and sons, apparently are never in sync.

I am sure that in a muddy field near Glastonbury, in a haze of smoke pulsing to the thud of a distant rock band, many a gap year student has contemplated how even if our watches were synchronised, the longevity of the journey is all our very own. And if one is in the depths of some great void in space one will never know for sure if one’s time is the same as anyone else's. I mention this because I recall now that I had a long pony tail when I visited the monastery. I had no great illusions about the wisdom of the east and recall how I was sure the Buddha would have smiled at the irony of the Dongshan monk who showed us around, wearing a big chunky Rolex. My father thought it was probably a fake.

There are many paths up the mountain and no place in this universe is special. One can set one’s watch by anything one wishes. We can all run on our own time if we so desire, though things seem to get organised if one sets it according to what everyone else’s watch says. Few of us manage to pull that off though and I am horribly punctual, thus forever irritated by British plumbers’ inability to arrive the same day as they told you they would arrive.

When my mother died, I found her diary of the trip. In between the mostly empty pages there were a few blurred discoloured photos taken with a disposable camera: there were some bicycles, a statue, the back of someone’s head, an under exposed one of The Pearl River at night, I think. She wrote things like: “rode on a bicycle rickshaw, ate black bean and chicken, hotel nice, city is very crowded.” Everything could have been read in any order, and could have referred to any time and place. My time with my parents was, I am sure, important to me and maybe them too. There were no pictures of me though. And no mention in the diary. It was an aid memoire for a mind no longer in the business of remembering anything.

Meanwhile, in another time and place, in the Guanzhou restaurant where our tour group ate, I mistakenly paid for someone else’s coca cola. One of the other tourists wanted a drink that was not on the prepaid tour group’s menu and I showed off with my Cantonese explaining to the bewildered waitress, that the tourist would pay extra. And so, in the confusion, I got the bill rather than the tourist who got his can of coke for free and disappeared. My father was not impressed. But I thought he might have been by the bit of Cantonese that I knew, and hoped he had not noticed the embarrassing fumbling of cash and confusion. Perhaps I should not remember that. Perhaps I should construct a different retrospective life, one pertaining to my own private highly preferential universe, the mountain top travelled by my own route - the mountain not there, with a non-existent route, travelled by no-one.

I can see the look on my parents’ faces as I tried to translate the explanation the monk gave of the meaning of the Bodhi Tree poem. It was engraved on a tin plate brutally nailed to the invaluable tree. I can see the nails. I can see the rust.

Let me just recollect a moment at a party with a scratchy LP of The Third Ear Band meandering through its Easternish tones, while I and my hairy pals sat around like sullen mushrooms in the dark, soaking up the vibe. There was no build and drop of the incessant House Music thud. Those were times before the invention of Disco, let alone its transition into House, and Ibiza was an unknown backwater. It was long before conversations with old pals lapsed into a litany of complaints about NHS tardiness and the number of pills one had to take to keep functioning at all. Pills were taken for a different reason back then and conversation turned to such things as how Time is not only mixed up with place, but also with scale! Go big, and time is irrelevant, and everything seems to happen all at once with no cause, no effect. And this 'Once' means nothing when talking about infinities. Infinite infinities branch off in all directions, creating universes forever until we run out of mathematics to describe it all. We can imagine a time and place where we have whatever we wish for, but it is never the time and place we live in. Wow! Yeah! Physics departments around the world were on the brink of an invasion by hairy guys with cosmic dreams.

On the small scale, the very small scale, before we hit an infinitely unfathomable barrier, we know that some things take place in several places at once, some things communicate over infinite distances instantaneously, and those Nobel prize winning experiments with photons indicate that effect can precede the cause, giving rise to thoughts of time travel. And there are those who suggest that time has more directions than just forwards and backwards but has many spiralling twists and loops. Thus, in some way, in some universe, we could go back and rectify the mistakes we made, assuming we remembered what they were. And we could experience the many possibilities that we could not decide between.

If only we think small enough. If only we could see into our brains, into the cells, into the atoms, the quarks, the strings of vibrating energy where potential is real, and the secrets are many. But the alarm bells are always ringing, and they are big; they start the race and finish it, leaving us no time to dig so far down, no time to avoid, no time to think, no time at all to stop it just hurling what it wills at us. It is a dark blur of random reflections upon the Pearl River. It is a scratchy LP stuck in a groove sounding surprisingly cool and ripe for sampling. Scientists at CERN are nodding sagely at these party time thoughts as another influx of Chinese postdocs arrive.

My mother, I recall, did not like the tea on the river trip we took. I told her that she had to have it. My father wondered if they had beer. No, I insisted, you have to have tea. I wanted them to see the performance where the char si fu delivers a metal tray with little tea cups and then deftly pours the gung fu cha from a huge tea pot with a very long spout. Not easy on a rocking boat. And I explained how this aeriated the tea and was thought to give it a delicate exquisite flavour, according to the tea aficionados of China. My parents thought it was a lot of fuss for something not much more than slightly dark warm water. The depths of eastern thought, so enticing to me, were just that, a lot of fuss about nothing much.

And now I, steeped in this, archaic melancholy steam driven time, glance at those tattooed masters of today’s Britain and can see that the intelligence in control of their time is as artificial as mine. The matri-patri-arch of this monastery, AI SiFu, neither fears time’s passage nor yearns for its return. It, or they, or whatever, is not plagued by nostalgia, nor burdened by the weight of unfulfilled dreams, nor for that matter committed to any sense of now. Time is always variable in an equation, a parameter in an algorithm, as easily adjusted as the volume on the iPod. It is kept by Alexa and Siri and other digital beings. They remind us of the birth of those we once encountered but have long forgot. They tell us of events that we once thought we should attend to but would have faded from our memory as other interests emerge. Appointments, deadlines, schedules and anniversaries are dictated not by human need or desire, and thus nothing can be mistimed, misunderstood, or missed at all. Whatever landed in our contacts list, or was whispered and overheard by our ever-listening phone, is fed to us as constant reminders or what might be real or might not.

This cold, unyielding logic of an app, sends me “friend” requests from my dead father’s hacked FaceBook page. I assume it is hacked, and not a message from another time, another place, another universe. Yes, I assume that this time is not just mis-forgotten, but merely reaching for my credit card. I can see the smiling monk with his Rolex. He knows things. Just not the things you think he should know. The fifth patriarch of the Dongshan monastery spent a lot of time contemplating what it was that one really should know. Consequently, he made a controversial decision.

An illiterate kitchen worker at the Dongshan Monastery, Huineng, added another verse to Shenxiu’s poem:

Bodhi was originally not a tree;

The bright mirror was also not a mirror.

In essence there is not a single thing.

Where could any dust be attracted?

The Fifth Patriarch appointed Huineng the Sixth Patriarch and I once snapped a branch from that Bodhi tree when the monks were not looking.

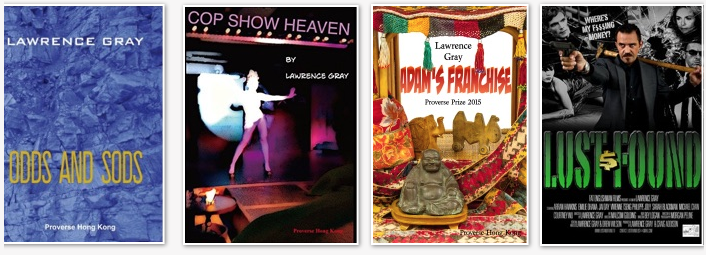

And while I have your attention, why not head over to the Goodness Grays YouTube Channel and check out our vlogs about our return to the UK after thirty years in Asia, not to mention our documentaries about Johor, our trips around Spain, Iceland, Tanzania, Malaysia and much more.

So Subscribe so that you can be informed when new series and Vlogs emerge.

Head off to GOODNESS GRAYS